The effect of ENSO on Australian rainfall

|

E. Linacre and B. Geerts |

3/’02 |

|

An El Niño tends to be accompanied by less rain across Australia, especially during the winter in the interior of eastern Australia, and during the northern Australian monsoon (1). La Niña years are often wetter, for instance the 1998-99 La Niña brought record level rains to parts of central Western Australia. Lake Eyre in the northeast of South Australia is dry except for occasional major flooding, usually during La Niña years, due to extra rainfall in southwestern Queensland (2). The past history of such heavy northern rainfalls can be inferred from coral striations at the mouth of river such as the Burdekin. To better understand the effect of El Niño Southern Oscillation on rainfall in Australia one can discriminate whether or not there is (3):

Such labelling can be matched against the occurrence of floods and droughts in Australia. It turns out that between 1871-1990 there were (3)-

|

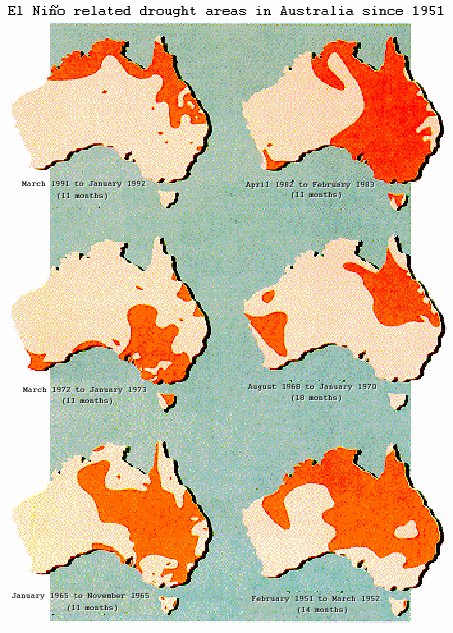

Fig 1. Drought regions during 6 El Niño events in Australia (source: Bureau of Meteorology). |

However, predictions of droughts based on these criteria alone would be wrong on 50% of occasions. In fact there are large differences between El Niño events (Fig 1), suggesting that some other interannual variation affects Australian rainfall patterns.

The intense El Niño of 1982-83 brought widespread drought to mainly eastern Australia, and the Ash Wednesday bushfires around Melbourne are not easily forgotten. But drought during the latest intense El Niño event (1997-98) was only local and not severe. Rainfall was quite normal over much of the region, and there was severe flooding along parts of the eastern coastline. Darwin received more rain than normal, whereas Indonesia (mainly Sumatra and Borneo) suffered from drought.

During this El Niño event, a significant El Niño-like near-coastal ocean warming has been observed along the western equatorial Indian Ocean (4). Other El Niño events have not witnessed this, or at least not as significantly. This may have enhanced the subsidence over Indonesia, leading to an unusual drought there, and it was responsible for the heavy rains from Kenya to Somalia in October-November, i.e. after the normal end of the wet season.

It appears the effect of ENSO on modulating Australia's rainfall variability is at least as important as its effect on the rainfall mean. For instance, the correlation of the SOI and rainfall (either in summer or winter) in Queensland has varied over roughly 20-year periods during the 20th century, being high for summer rainfalls during 1900-35 and 1940-1990, but negative during 1928-48, for instance. The standard deviation of rainfalls during the 20-year periods, i.e. the variability, fluctuated in parallel with the correlation coefficient (5).

Sometimes higher-than-normal temperatures occur during El Niño events, mainly because of increased daytime maxima. Higher surface maxima may imply more frequent thunderstorms, and in fact, the higher the SOI (i.e. under La Niña conditions) the higher the continent-average amount of rain per rain event in Australia.

In summary, the relations between SOI and rainfall and mainly between SOI and temperature are rather poor in Australia. They appear to have changed a little around 1975 (1), coincidentally with several other climate changes around the world. For instance, the global mean temperature was steady from the 1940’s until the mid-70’s, and it rose rapidly thereafter. In Australia recent La Niña years (cold phase) tend to be warmer than El Niño years (warm phase) before 1975. It is suggested that this and other changes may be related to a warming trend of the eastern Indian Ocean during the last few decades (1).

References

- Nicholls, N. B. Lavery, C. Friedericksen, W. Drodowsky & S. Torok 1996. Recent apparent changes in relationships between the ENSO and Australian rainfall and temperature. Geophys. Res. Letters 23, 3357-60.

- Kotwicki, V. & R. Allan* 1999. La Nina de Australia - contemporary and paleohydrology of Lake Eyre. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 144, 265-80.

- Kane, R.P. 1997. On the relationship of ENSO with rainfall over different parts of Australia. Aust. Meteor. Mag., 46, 39-49.

- Webster, P. 1998: Personal communication

- Lough, J.M. 1999. Northeast Australian climate and the changing role of El Nino-Southern Oscillation. Preprints for the 10th Symp. on Global Change Studies, Dallas, 10-15th January (Amer. Meteor. Soc.), 342-344.